Comics & Video Games

The youngest member of the arts family, video games can be broadly defined as electronic games with an interactive interface and a visual video display.

Comic Books and video games share many structures, notably that of sequentialism. One of the key elements of the comic book is the work done by the reader to connect a story’s individual panels into a cohesive whole. We can see a similarity with the common structure of multiple “levels” in a video game, which the player either narratively connects on their own, or frequently are connected by “cinematic cut scenes” that introduce additional plot elements and characters (another example of a mixing of multiple art forms in a single work).

The creative process of creating video games also borrows much from the general traditions of the comic book, with drawn characters acting out a fictional plot line in richly imagined locales.

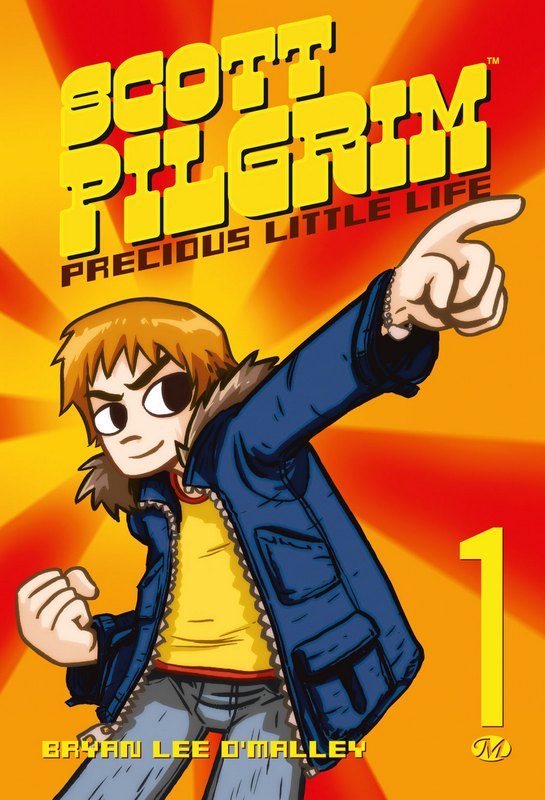

We also find frequent borrowings of specific “comic book” codes in video games, such as the use of bold onomatopeias like “Biff! Bang! Pow!” This of course goes both ways; the Canadian graphic novel series Scott Pilgrim by Brian Lee O’Malley is explicitly modeled on the structure of a video game. The eponymous hero falls for the beautiful Ramona Flowers and, to prove his love, must defeat her “Seven Evil Exes,” who serve as “boss fights” and are rendered in a style that hearlens to vintage “beat-’em-up” games. Scott Pilgrim went on to be adapted into both a film and a purposefully “old-school” video game, bringing the references full circle.

Interactive Comics and Escapist Universes

In the burgeoning field of interactive comics, the reader takes on a more active role that will be familiar to players of video games, guiding the hero through a series of decisions and creating the storyline. This format has been promoted by a variety of media outlets, including France 24’s Iranorama, in which the player takes on the role of a journalist during a presidential election in Iran, and Anne Frank au pays du manga, published by Arte, which uses an interactive narrative to draw parralels between the Holocaust and the droping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

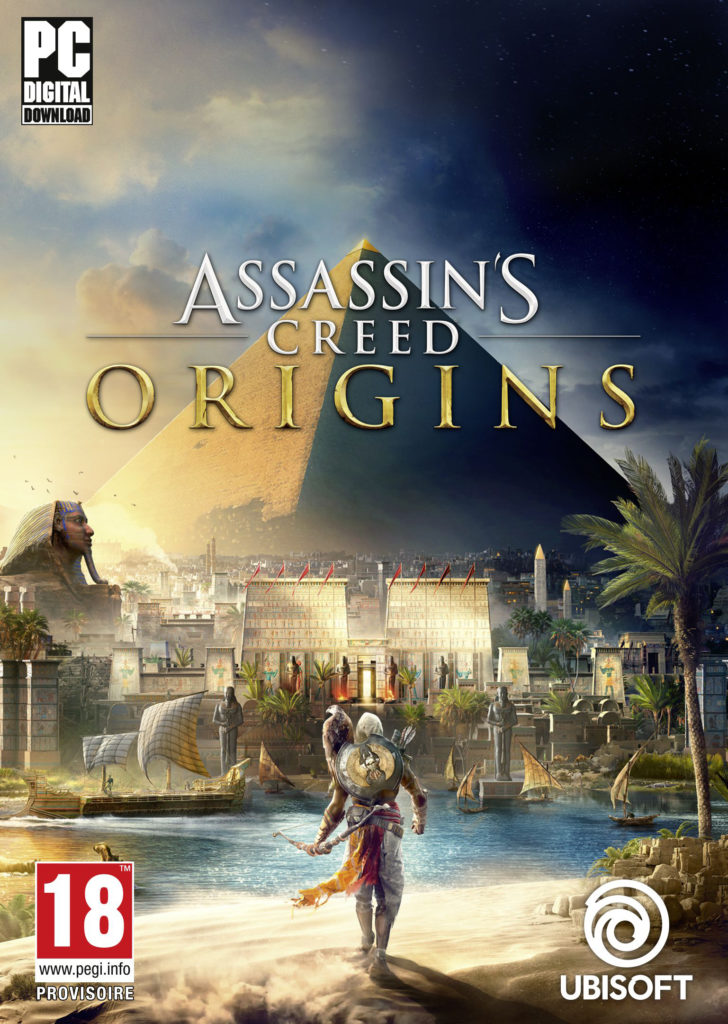

On the other end of the spectrum, we often find that video games and comics are both frequently interested in escapist entertainment, with a focus on the sci-fi and fantasy genres, a version of the classic “quest narrative,” spectacular fights, the hero’s journey. While no one would suggest that comics and video games are limited only to these subjects, the enduring appeal of this classic formula in both mediums speaks to their linked aesthetic sensibilities.

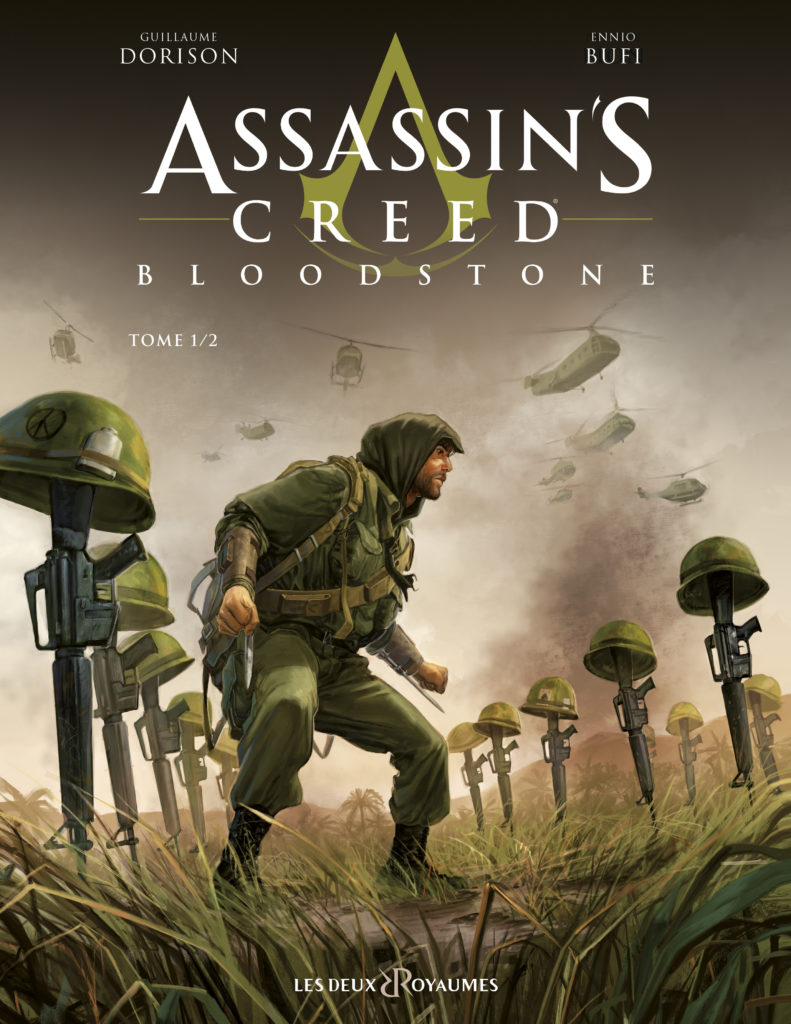

For some narratives, the opportunity to describe a fictional universe in both video games and comic books can permit considerably more freedom. Video games, famously tolerant of violence, are far less comfortable with nudity and other taboos more easily accepted in comics. Comics also allow for complex or difficult subject matter, such as politics or history, to be dealt with at greater length than are allowed in the rhythms of the video game. Comic book adaptations thus can be used to expand the narratives of video games, and can even become a veritable artistic vision on their own merits.

For example, the two volumes of Assassin’s Creed Bloodstone allow the authors to explore elements of the game’s narrative in greater depth, creating a complementary story for fans of the video game franchise that mixes the visual codes of both comics and video games.

Want to know more?

- Game Over, Bad Cave, Adam & Midam (2019, Glénat)

- Dofus, t. 22 : Les merveilleuses cités gores, Tot & Ancestral Z (2015, Ankama)

- Homestuck, Andrew Hussie (2009, Webcomic)