Comics & Architecture

Architecture, traditionally considered the first of all the arts, can be defined as the conception of buildings and spaces in a manner that respects both the practical requirements of construction and the more lofty codes of aesthetics. These considerations obviously change depending on the function of the final building (religious, institutional, defensive, etc).

Urbanism is an important theme in comic books, which have so often become a sort of laboratory for imagining the “City of Tomorrow.” These futuristic urban utopias, seen most frequently in the pages of science fiction stories, inspired architects, whose creations in turn provided fodder for more comic books stories. One of the most telling examples can be found in the magazine Archigram, a 1960s avant-garde architecture revue which was inspired by futurist culture and served as a platform for its further development.

Both the architect and the cartoonist have long used similar tools, from the traditional drafting pens and straight edges to today’s state-of-the-art digital drawing software. Both seek to “insert life into the heart of a living space,” and to have their creations reflect society. Despite the obvious differences in scale, this complementary approach allows the two arts to respond and influence each other in surprising ways. There is a reciprocal impregnation of the universes.

The City as a Protagonist

The city can often seem like a character in and of itself, and in certain comic books the unique urban setting, be it fictional or real, can even take on a central role in the narrative.

Famed real-world locations like New York, London, Paris, and Tokyo are all seemingly-inexhaustible sources of inspiration that have left their distinctive mark on the landscape of comic books. Perhaps just as well-known are imaginary places such as Gotham City, whose dark shadows shelter the superhero Batman. Superman’s fictional home takes its name from the film Metropolis by Fritz Lang (1927), showcasing the fluid influences between comic books and cinema and architecture: The futuristic cityscapes of Metropolis strongly influenced later representations of the city in comic books, and Fritz Lang was himself inspired by the work of Antonio Sant’Elia, an Italian architect and member of the Futurist movement. It all comes full circle.

Les Cités obscures by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters (1983, Casterman) is another excellent example of the enduring importance of architecture in comic books (on the right). Cities and urbans space are of central importance in this series of graphic novels set on an alternate “Counter-Earth,” including fictional versions of real European cities, playfully renamed: Brussels here becomes Brüsel and Paris is transformed into Pâhry.

(2009, Philippe Picquier)

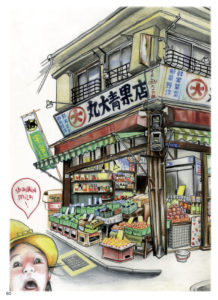

The city can also be a more intimate space, revealed in fleeting glimpses: A quiet walk along a canal or through the backstreets, everyday urban adventures that might seem quotidian but reveal so much about the urban environment’s influence on the individual.

The City: a Playground for the Creators

Cities and buildings can also get in the game, with the walls of many urban spaces adorned with famed comic characters. Brussels is the perfect example, proudly displaying its unique cultural heritage around each corner along the Comic Strip Route with nearly sixty frescoes highlighting works by Belgian cartoonists scattered across the city’s walls.

© Froud et Stouf, fresque murale Parcours BD Bruxelles

© Quick et Flupke, fresque murale Parcours BD Bruxelles

© Corto Maltese, fresque murale Parcours BD Bruxelles

Want to know more?

- Le Corbusier, architecte parmi les hommes, Frédéric Rébéna and Jean-Marc Thévenet (2010, Dupuis)

- Sin City, Frank Miller (1991, Dark Horse Comics)

- Les Cités Obscures, François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters (1983, Casterman)